|

restoring our biblical and constitutional foundations

|

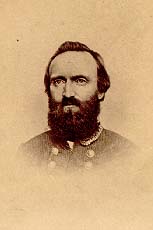

The Day “Thomas Jonathan” Became “Stonewall”

Exactly 142 years ago today, July 21, the names Bull Run and Manassas meant virtually nothing throughout the nation. By nightfall they had become immortal, as had another name, “Stonewall.” The first major engagement of the “Civil” War was now history.

The Federal commander was only 43 years old and only two months a brigadier general. A physically powerful man, Irvin McDowell was admired as an officer well-informed both in and out of his profession. He had been educated in France and West Point, and had distinguished himself in the Mexican War. He had served on the staff of General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, actually a year older than the Federal Constitution over whose interpretation the two nations were doing battle. McDowell knew that the 30,000 troops under his command were mostly untrained, but the word was “go,” and away they went.

The Southerners were prepared, however. On May 8, only four companies of infantry and cavalry had been stationed at Manassas Junction. But before the month was out, another brigade had arrived, and on June 1 Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the hero of Sumter, assumed command of the entire Confederate forces in northeastern Virginia.

On July 17, the Federal troops pushed ten miles from Washington City to Fairfax Courthouse, where they paraded through town four abreast, with bands playing and flags waving. Already the Federals were clogging the roads out of the Federal capitol, and by the 18th were gathering along the heights of Centerville. Here the Confederate forces lay along an eight-mile stretch of Bull Run creek. Beauregard sent a message by telegraph to Richmond informing the Confederate president that his outposts had been attacked and requesting reinforcements “at the earliest possible instant and to every possible means.”

General Joseph Johnston immediately made plans to leave the Shenandoah Valley. He began moving his army thorough Ashby’s Gap to Piedmont, a station on the Manassas Gap line. Meanwhile, the bivouacs of the Union soldiers swarmed with visitors both during the 19th and 20th. Many of them had come out from Washington in carriages, and some of the women had even packed their fineries, knowing that there would be dancing at Fairfax Courthouse after the Yankees had driven the Southerners back to Richmond.

Johnston stepped off the train at Manassas, having eluded Union General Patterson without trouble. At 6:30 am on the 21st, Beauregard, directing action with Johnston’s approval, received a message that some 1,200 men were deployed in his front. Although he had prepared an offensive plan, he now knew that the Federals had taken the initiative away from him. Beauregard ordered T. J. Jackson’s brigade to take up such positions along Bull Run that he would able to reinforce either flank of the Confederate army.

As

the Federal attackers seemed about to win the day, Jackson’s troops stood

fast and helped turn the tide. Confederate general Bernard Bee is said to

have exclaimed to his own troops: “Look! There stands Jackson like a stone

wall!” The nickname stuck. Jackson’s fame was carried with it across the

South and later the nation, and few would know him today by his real

name—Thomas Jonathan. Ironically, it wasn’t as a “stone wall” but as a

lightning bolt—a tactical genius and hard-striking offensive master—that

Jackson achieved his greatness. In his Valley Campaign in 1862 he eluded,

then defeated, superior Federal forces, and in August of the same year he

marched entirely around the Union army of General John Pope, then stood on

the defensive, luring Pope to the attack until the rest of the Confederate

army could join in a crushing counterattack and victory at the Second

Manassas.

As

the Federal attackers seemed about to win the day, Jackson’s troops stood

fast and helped turn the tide. Confederate general Bernard Bee is said to

have exclaimed to his own troops: “Look! There stands Jackson like a stone

wall!” The nickname stuck. Jackson’s fame was carried with it across the

South and later the nation, and few would know him today by his real

name—Thomas Jonathan. Ironically, it wasn’t as a “stone wall” but as a

lightning bolt—a tactical genius and hard-striking offensive master—that

Jackson achieved his greatness. In his Valley Campaign in 1862 he eluded,

then defeated, superior Federal forces, and in August of the same year he

marched entirely around the Union army of General John Pope, then stood on

the defensive, luring Pope to the attack until the rest of the Confederate

army could join in a crushing counterattack and victory at the Second

Manassas.

142 years after the Battle of First Manassas it is fascinating to read Jackson’s own report:

About 4 in the morning I

received notice from General Longstreet that he needed a re-enforcement of

two regiments, which were accordingly ordered.

Subsequently I received an order from General Beauregard to move to the

support of General Bonham, afterwards to support General Cocke, and

finally to take such position as would enable me to re-enforce either, as

circumstances might require.

Whilst in the position last indicated I received a request from General

Cocke to guard the stone bridge, and immediately moved forward to effect

the object in view.

Subsequently ascertaining that General Bee, who was on the left of our

line, was hard pressed, I marched to his assistance, notifying him at the

same time that I was advancing to his support; but, before arriving within

cannon range of the enemy, I met General Bee’s forces falling back. I

continued to advance with the understanding that he would form in my rear.

His battery, under its dauntless commander, Captain Imboden, reversed and

advanced with my brigade.

The first favorable position for meeting the enemy was at the next summit,

where, at 11.30 a.m., I posted Captain Imboden’s battery and two pieces of

Captain Stanard’s, so as to play upon the advancing foe. The Fourth

Regiment, commanded by Col. James F. Preston, and the Twenty-seventh

Regiment, commanded by Lieut. Col. John Echols, were posted in rear of the

batteries; the Fifth Regiment, commanded by Col. Kenton Harper, was posted

on the right of the batteries; the Second Regiment, commanded by Col.

James W. Allen, on the left, and the Thirty-third, commanded by Col. A. C.

Cummings, on his left. I also ordered forward the other two pieces of

Captain Stanard’s and all those of Colonel Pendleton’s battery. They, as

well as the battery under Lieutenant Pelham, came into action on the same

line as the others; and nobly did the artillery maintain its position for

hours against the enemy’s advancing thousands. Great praise is due to

Colonel Pendleton and the other officers and men.

Apprehensive lest my flanks should be turned, I sent an order to Colonels

Stuart and Radford, of the cavalry, to secure them. Colonel Stuart and

that part of his command with him deserve great praise for the promptness

with which they moved to my left and secured the flank by timely charging

the enemy and driving him back.

General Bee, with his rallied troops, soon marched to my support and as

re-enforcements continued to arrive General Beauregard posted them so as

to strengthen the flanks of my brigade. The enemy not being able to force

our lines by a direct fire of artillery, inclined part of his batteries to

the right, so as to obtain an oblique fire; but in doing so exposed his

pieces to a more destructive fire from our artillery, and one of his

batteries was thrown so near to Colonel Cummings that it fell into his

hands in consequence of his having made a gallant charge on it with his

regiment; but owing to a destructive small-arm fire from the enemy he was

forced to abandon it. At 3.30 p.m. the advance of the enemy having reached

a position which called for the use of the bayonet, I gave the command for

the charge of the more than brave Fourth and Twenty-seventh, and, under

commanders worthy of such regiments, they, in the order in which they were

posted, rushed forward obliquely to the left of our batteries, and through

the blessing of God, who gave us the victory, pierced the enemy’s center,

and by co-operating with the victorious Fifth and other forces soon placed

the field essentially in our possession.

About the time that Colonel Preston passed our artillery the heroic

Lieutenant-Colonel Lackland, of the Second Regiment, followed by the

highly meritorious right of the Second, took possession of and endeavored

to remove from the field the battery which Colonel Cummings had previously

been forced to abandon; but after removing one of the pieces some distance

was also forced by the enemy’s fire to abandon it.

The brigade, in connection with other troops, took seven field pieces in

addition to the battery captured by Colonel Cummings. The enemy, though

repulsed in the center, succeeded in turning our flanks. But their

batteries having been disabled by our fire, and also abandoned by reason

of the infantry charges, the victory was soon completed by the fire of

small-arms and occasional shots from a part of our artillery, which I

posted on the next crest in rear.

By direction of General Johnston I assumed the command of all the

remaining artillery and infantry of the Army near the Lewis house, to act

as circumstances might require. Part of this artillery fired on the

retreating enemy. The colors of the First Michigan Regiment and an

artillery flag were captured—the first by the Twenty-seventh Regiment and

the other by the Fourth.

Lieut. Col. F. B. Jones, acting assistant adjutant-general; Lieut. T. G. Lee, aide-de-camp, and Lieut. A. S. Pendleton, brigade ordnance officer, and Capt. Thomas Marshall, volunteer aide, rendered valuable service. Cadets J. W. Thompson and N. W. Lee, also volunteer aides, merit special praise. Dr. Hunter H. McGuire has proved himself to be eminently qualified for his position—that of medical director of the brigade. Capt. Thomas L. Preston, though not of my command, rendered valuable service during the action.

Finally, in a letter to his wife dated July 23, 1861, Jackson, with characteristic humility, wrote:

My Precious Pet, Yesterday we fought a great battle and gained a great victory, for which all the glory is due to God alone. Although under a heavy fire for several continuous hours, I received only one wound, the breaking of the longest finger of my left hand; but the doctor says the finger can be saved. It was broken about midway between the hand and knuckle, the ball passing on the side next the forefinger. Had it struck the centre, I should have lost the finger. My horse was wounded, but not killed. Your coat got an ugly wound near the hip, but my servant, who is very handy, has so far repaired it that it doesn’t show very much. My preservation was entirely due, as was the glorious victory, to our God, to whom be all the honor, praise and glory. The battle was the hardest that I have ever been in, but not near so hot in its fire. I commanded the centre more particularly, though one of my regiments extended to the right for some distance. There were other commanders on my right and left. Whilst great credit is due to other parts of our gallant army, God made my brigade more instrumental than any other in repulsing the main attack. This is for your information only, say nothing about it. Let others speak praise, not myself.

Without doubt, Jackson’s most effective military quality was his decisiveness. Seeing opportunities quickly, he seized them at once and never hesitated to attack even superior forces if he saw the possibility of advantage. He may well have been, and some authorities consider him, the war’s most remarkable soldier.

In honor of this great soldier and Christian, perhaps you’d like to join me in a hearty rendition of “Stonewall Jackson’s Way”!

Come stack

arms, men! pile on the rails,

Stir up the campfire bright;

No growling if the canteen fails,

We’ll make a roaring night.

Here Shenandoah brawls along,

Three burly Blue Ridge echoes strong,

To swell the Brigade’s rousing song

Of “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

We see him now—the queer slouched hat

Cocked o’er his eye askew;

The Shrewed, dry smile; the speech so pat,

So calm, so blunt, so true.

The “Blue-light Elder” knows ‘em well;

Says he, “That’s Banks—he’s fond of shell;

Lord save his soul! We’ll give him—well!

That’s Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

Silence! ground arms! kneel all! caps off!

Old Massa’s goin’ to pray.

Strangle the fool that dares to scoff!

Attention! It’s his way.

Appealing from his native sod

In forma pauperis to God:

“Lay bare Thine arm; stretch forth Thy rod!

Amen!”— That’s Stonewall’s way.

He’s in the saddle now. Fall in!

Steady! the whole brigade!

Hill’s at the ford, cut off; we’ll win

His way out, ball and blade!

What matters if our shoes are worn?

What matters if our feet ore torn?

Quick step! We’re with him before morn’!

That’s “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

The sun’s bright lances rout the mists

Of morning and, by George!

Here’s Longstreet, struggling in the lists,

Hemmed in an ugly gorge.

Pope and his Dutchmen, whipped before;

”Bay’nets and grape!” hear Stonewall roar;

“George, Stuart! Pay off Ashby’s score!”

In “Stonewall Jackson’s way.”

Ah, Maiden! wait and watch and yearn

For news of Stonewall’s band.

Ah widow! read, with eyes that burn,

That ring upon thy hand.

Ah wife! sew on, pray on, hope on;

Thy life shall not be all forlorn;

The foe had better ne’er been born

That gets in “Stonewall’s way.”

July 21, 2003

David Alan Black is the editor of www.daveblackonline.com.