|

restoring our biblical and constitutional foundations

|

Reaching the Orthodox: What is the Orthodox Church?

It has been said that to be Ethiopian is to be Orthodox. Such is the influence of the Ethiopian Orthodox church upon the society. In our work in Ethiopia, God has placed us primarily in Muslim areas. We have not talked much about the Orthodox influence.

But now God has appointed us to begin a new work. In addition to working in Burji and in Alaba, God has appointed us to a brand new ministry of planting His Church in an area that is 99 percent Orthodox. (For the purposes of this discussion, “church” refers to the church as an institution/organization, and “Church” refers to the body of true believers; “church” is a man-made structure of religion, whereas “Church” is a spiritual work done by the Lord Jesus.)

We do not have many Orthodox churches here in America. The closest thing we have is Roman Catholicism. In fact, back in the history of Christendom, the Roman Catholic and the Orthodox churches were one and the same. If you remember your Christian history, in the first few hundred years after our Lord’s death and resurrection, the Body of Jesus met in homes, led by “non-professional” men, suffering greatly at the hands of non-believing Gentiles and Jews alike. The fellowship of the Churches was unstructured; there were no seminaries or formal Bible schools. The Gospel flowed from town to town as the people of God moved from town to town. Sometimes these people were sent by the Churches as missionaries (for example, Paul and Barnabas); sometimes they were just scattered by persecution (such as Priscilla and Aquila). But everywhere Christians went, they spoke of the Way of Jesus; theirs was a living testimony filled with the Spirit.

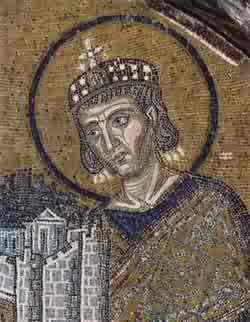

Then came Constantine. It was 312 years after the

birth of our Lord Jesus. As Constantine came to his final battle, the city

of Rome lay before him. Hailed as Augustus by his troops in the western

part of the

Roman

Empire, he was now conquering the eastern part to unite all of the Empire

under his leadership. He had a vision of a cross just prior to the battle.

In the confidence of that vision, he won the victory. And after the

victory, he pronounced that all his empire would become “Christian.” All

of his soldiers were baptized upon his command and a cross was painted on

their shields. Thus was born the “Holy Roman Empire.”

Roman

Empire, he was now conquering the eastern part to unite all of the Empire

under his leadership. He had a vision of a cross just prior to the battle.

In the confidence of that vision, he won the victory. And after the

victory, he pronounced that all his empire would become “Christian.” All

of his soldiers were baptized upon his command and a cross was painted on

their shields. Thus was born the “Holy Roman Empire.”

And what was the effect of this first “Christian”

Emperor upon the Lord’s Church? He ended the persecution of the Christians

through the Edict of Milan. He joined pagan things with Christian things

to form synergistic religion. (For example, the celebration of Christ’s

birth was joined to the worship of the birthday of the pagan sun god; this

sun god was Constantine’s favorite pagan god.) He built Christian

monuments and buildings beside pagan ones; the old St. Peter’s Basilica in

Rome and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem were built by him.

He gave some of the government functions to the church, such that the

church became an arm of the government. He called together councils of

church leaders to debate and decide doctrinal issues. (For example, the

Council of Nicea decided the canon of the Scriptures.) During the

structuring of his empire, the Bishop of Rome, the Bishop of Antioch, and

the Bishop of

Alexandria

were established; later the Bishop of Constantinople and the Bishop of

Jerusalem were added.

Alexandria

were established; later the Bishop of Constantinople and the Bishop of

Jerusalem were added.

In 330, Emperor Constantine decided to move the capital of the Roman Empire toward the East, so he developed the city of Constantinople as a “new Rome.” Upon his death he was named a saint by the Eastern Church, and is often referred to by that church as the “Thirteenth Apostle.”

From the beginning, the Bishop of Rome claimed

primary authority over the other Bishops, calling himself the Pope

(“Father”) as directly descended from the Apostle Peter. The Bishop of

Constantinople also claimed high authority, since he was in the “new

Rome.” The Eastern Bishops, called Patriarchs (“Fathers”), disallowed the

Bishop of Rome’s claim to primary authority. This strain in relationship

was deepened when the political structure of Rome was divided into Western

and Eastern regions, each with its own emperor. The Western Empire fell to

Germanic tribes, while the Eastern Empire (Byzantine) flourished. Also,

language barriers existed: the West spoke Latin, while the East spoke

Greek. Eventually Latin and Greek faded, replaced by numerous other

languages, and the West/East separation expanded as

communication

failed.

communication

failed.

In 1054 AD the leaders of the Western church excommunicated the leaders of the Eastern church, and visa versa. Although there were periods of semi-reconciliation, during the Fourth Crusade soldiers of the Western (Roman) church sacked Constantinople as they passed on their way to the Holy Land. This brutality finally divided the church into the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox. The Catholic-Orthodox Joint Declaration of 1965, read by Pope John Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I, officially reversed the bilateral excommunications of 1054, but did little to bring unification. In more recent years, the Patriarchs of various countries have visited the Vatican, and the last two Popes have visited countries at the invitation of their Orthodox Patriarchs.

So where does the Ethiopian Orthodox Church fit into all of this history? (See Part 3.)

August 10, 2007