|

restoring our biblical and constitutional foundations

|

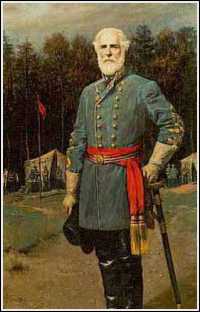

If people want to show respect for the Southern cause, they can begin by properly honoring the man who is perhaps its greatest hero, General Robert E. Lee. Many portrayals of Lee are, frankly, less than accurate. Rather than exalting his character, they diminish it—both literally and figuratively.

Take Lee’s physical height. If you were to ask people today what Lee looked like, many would respond, “Why, just like Martin Sheen in the movie.” The “movie,” of course, is Ted Turner’s $20 million Gettysburg, which has been called the most ambitious and magnificently flawed cinematic undertaking since Apocalypse Now. Unfortunately, Gettysburg fails to deliver the goods. It depicts the South’s greatest general—and arguably the greatest military leader who ever lived—as a dwarf-like creature astride a diminutive, clumsy horse. As movie critic Martin Treu has put it, “In scene after scene, General Robert E. Lee, a man of erect bearing just over 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighing 170 pounds is shown among men who tower over him, both on foot and on horseback. If this were the case, the entire Confederate army would have to have been over 6 feet 4 inches tall. The only people obviously shorter than Robert E. Lee, in this film, are the 12-year-old drummer boys.”

Treu’s conclusion? “The viewer is led to picture Robert E. Lee as a Leprechaun instead of the giant he was.”

Washington Post staff writer Ken Ringle agrees: “The film’s weakest role is its most crucial. Martin Sheen’s woolly-headed performance as Robert E. Lee conveys little of the character, charisma or aura of infallibility that made the legendary general the closest thing to a universal hero among the generals of the Civil War. Instead he emerges at film’s end as a kind of crazed religious mystic: a Confederate Jim Jones invoking his legions to bullets instead of poisoned Kool Aid for no more clearly discernible reason.”

The tragedy of Gettysburg is that Lee keeps getting smaller and smaller, until at the end we are left with little more than a stubby, hand-ringing neurotic who wonders out loud, “What now?”

Of course, none of this is historically accurate. Take the height issue. By the standards of his day, Lee was tall, and so was his horse. The real Traveller was fully 16 hands high and over 1300 pounds, but in Gettysburg the great charger is transformed into a stumpy pony-like animal tripping over itself. What is more, the real Lee was a superb horseman, having served as a Colonel in the cavalry. In Gettysburg, Sheen’s clumsy horsemanship is almost as inauthentic as his contrived Southern accent.

In addition to the photographs taken of Lee during his lifetime, we are fortunate to have a number of written descriptions of his appearance. What is surprising is the large number of references to Lee’s height. He was, apparently, considerably taller than most men of his day. After Lee had visited Fort Sumter in 1861, a soldier gave the following description:

Glancing round we saw approaching us the then commander of the fort, accompanied by several of his captains and lieutenants; and, in the middle of the group, topping the tallest by half a head, was, perhaps, the most striking figure we had ever encountered, the figure of a man seemingly about fifty-six or fifty-eight years of age, erect as a poplar, yet lithe and graceful, with broad shoulders well thrown back, a fine, justly-proportioned head posed in unconscious dignity, clear, deep, thoughtful eyes, and the quiet, dauntless step of one every inch the gentleman and soldier.... And this superb soldier, the glamour of the antique days about him, was no other than Robert E. Lee, just commissioned by the President, after his unfortunate campaign in Western Virginia, to travel southward and examine the condition of our coast fortifications and seaboard defenses in general....

At Appomattox, a Northern newspaper correspondent wrote:

General Lee looked very much jaded and worn, but nevertheless presented the same magnificent physique for which he has always been noted. He was neatly dressed in gray cloth, without embroidery or any insignia of rank, except the three stars worn on the turned portion of his coat-collar. His cheeks were very much bronzed by exposure, but still shone ruddy underneath it all. He is growing quite bald, and wears one of the side locks of his hair thrown across the upper portion of his forehead, which is as white and fair as a woman’s. He stands fully six feet one inch in height, and weighs something over two hundred pounds, without being burdened with a pound of superfluous flesh. During the whole interview he was retired and dignified to a degree bordering on taciturnity, but was free from all exhibition of temper or mortification. His demeanor was that of a thoroughly possessed gentleman who had a very disagreeable duty to perform, but was determined to get through it as well and as soon as he could.

Finally, upon Lee’s death the New York Herald ran an obituary that included the following description:

In person General Lee was a notably handsome man. He was tall of stature, and admirably proportioned; his features were regular and most amiable in appearance, and in his manners he was courteous and dignified.

There you have it—Lee was tall, and strikingly handsome to boot! It is historically inaccurate to portray him as anything less. And it is only a short hop from depicting Lee as a stubby historical figure (as in Gettysburg) to the conclusion that his ideas were small.

Etymologically, the word “tall” comes from the Old English getael, meaning “swift,” “brave,” or “quick.” The word was synonymous with “courageous.” This metaphorical meaning can, of course, also be applied to Lee.

Lee was a man’s man. He was the idol of his

people, men and women alike. Mary Chestnut, the famous Richmond diarist,

called him “the portrait of a soldier.” A British journalist said he was

“the handsomest man I ever saw.” Confederate General Clement Evans

described Lee as “...nearest approaching the character of the great and

good

George

Washington than any living man. He is the only man living in whom the

soldiers would unconditionally trust all their power for the preservation

of their independence.” And Theodore Roosevelt, of New York, wrote, “The

world has never seen better soldiers than those who followed Lee, and

their leader will undoubtedly rank as, without any exception, the very

greatest of all great captains that the English speaking peoples have

brought forth.”

George

Washington than any living man. He is the only man living in whom the

soldiers would unconditionally trust all their power for the preservation

of their independence.” And Theodore Roosevelt, of New York, wrote, “The

world has never seen better soldiers than those who followed Lee, and

their leader will undoubtedly rank as, without any exception, the very

greatest of all great captains that the English speaking peoples have

brought forth.”

Among the many outstanding qualities of Lee’s character, his Christian faith was paramount. Indeed, our Confederate ancestors, regardless of their church affiliations, were uncompromising defenders of orthodox Christianity. To leave the Christian element out of the Southern drive for independence would be like trying to describe Switzerland without mentioning the Alps. Not for one moment did our ancestors think their own unaided efforts could achieve victory.

Lee had learned through personal hardship and tragedy to possess an unrelenting faith in the sovereign counsel of God, both in personal and national matters. Upon hearing of the death of his 23-year-old daughter, Annie, and unable to attend her funeral, he insisted that these words be carved on her tombstone: “Perfect and true are all His ways, whom Heaven adores and earth obeys.” As for his views on the Bible, Lee once remarked to Chaplain William Jones: “There are things in the Old Book which I may not be able to explain, but I fully accept it as the infallible Word of God, and receive its teachings as inspired by the Holy Spirit.”

On Lee’s humility, John Cooke, in his Life of General Robert E. Lee, wrote: “The crowning grace of this man, who was thus not only great but good, was the humility and trust in God, which lay at the foundation of his character.” Cooke then added: “He had lived, as he died, with this supreme trust in an overruling and merciful Providence; and this sentiment, pervading his whole being, was the origin of that august calmness with which he greeted the most crushing disasters of his military career. His faith and humble trust sustained him after the war, when the woes of the South wellnigh broke his great spirit; and he calmly expired, as a weary child falls, asleep, knowing that its father is near.”

Finally, Lee considered himself a sinner who had been saved, not by church attendance or by good works or by any other human endeavor, but solely by the grace of God and the blood of Christ. In his Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee, the Rev. J. William Jones, who was Lee’s chaplain at Washington College, wrote: “If I ever come in contact with a sincere, devout Christian—one who, seeing himself to be a sinner, trusted alone in the merits of Christ, who humbly tried to walk the path of duty, ‘looking unto Jesus’ as the author and finisher of his faith, and whose piety constantly exhibited itself in his daily life—that man was General R. E. Lee.”

There are Southerners today who would prefer to leave the Christian element out of our drive to return America to its constitutional foundations. Such people betray not only our Lord and Savior but also the memory of such Confederate leaders as Davis, Lee, Jackson, Early, and many others. These were men whose every thought, word, and deed derived from a belief in the saving work of Christ and the sovereignty of God. People who deny this Christian influence fail to grasp one of the most fundamental facts about Lee: that he was devoted to the Southern cause precisely because of his devotion to Jesus Christ.

Lee’s Christian faith determined how he lived his entire life, and it alone can explain his intense devotion to duty. The greatest injustice we can do to Lee is to make him out as some secular hero or, worse yet, as a spiritual and intellectual buffoon.

As a lasting tribute to a man of sterling Christian character and Southern patriotism, Benjamin Harvey Hill gave us these words in his address before the Southern Historical Society on February 18, 1874, just four years after Lee’s death:

When the future historian shall come to survey the character of Lee, he will find it rising like a huge mountain above the undulating plain of humanity, and he must lift his eyes high toward heaven to catch its summit. He was a foe without hate, a friend without treachery, a soldier without cruelty, a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices, a private citizen without wrong, a neighbor without reproach, a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar without his ambition, a Frederick without his tyranny, a Napoleon without his selfishness, and a Washington without his reward.

If I had to pick one American to represent the best values in our nation, that man would be Robert E. Lee. He stands taller than anyone else. But to see him you must lift your eyes “high toward heaven.”

January 19, 2006

David Alan Black is the editor of www.daveblackonline.com.